The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

The effect of the first difference is, on the one hand, to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations.

If that last part doesn't make your heart ache with nostalgia then you haven't paid much attention to U.S. politics for a long time. I personally cannot remember a time, and perhaps no one alive can remember a time, when the Congress of the United States consisted chiefly of citizens with enough wisdom, patriotism, and love of justice to refuse a lobbyist or vote against a good pork barrel spending bill in order to get reelected.

What happened? Are people fundamentally more corrupt than in the past? No, we are generally as selfish as always. The problem is, we have outgrown our system of government. Again. The brilliant idea of a republic, electing a small body of representatives who then govern among themselves by direct democracy (more or less), is inherently more scalable than pure democracy, but it also has its limits. Our numerous modern representatives — presidents, electors, congressmen, judges, mayors, city council members, constables (whatever those are) and so on — are often elected based not on their character, but on superficial bases like parentage, wealth, party affiliation, and hair style. That's largely because nobody has the time to really know and understand who these people are. And so we bestow enormous, disproportionate voting power to people based on silly criteria, including what they say they'll do in office, because we just don't have the time to examine their history to determine what they really believe in.

The answer, or at least one answer, can be found in the Ethosphere. Instead of voting for people to represent us, we might vote only on ideas, or their written embodiment that we call props. It's much easier to decide whether you are for or against an idea, a proposal, or a proposition, than it is to decide whether a complex person will be more or less likely to represent your own views. In order to scale, there will still be some citizens who have more voting power than others, but these representatives will be chosen based solely on their history of constructive participation in whatever society you both choose to be members. Citizens who write props that are eventually ratified by the voters at large will receive more voting power, as a side-effect of the normal activity of the group. Representatives can get elected only by constructive participation, not by campaigning.

This idea of conveying greater resources, in this case voting power or rep, to some individuals in order to increase the welfare of the entire group was first identified and discussed by a nineteenth century economist named Vilfredo Pareto. Pareto Inequality is exactly this somewhat paradoxical idea that the overall social welfare (measured by some metric) of a society can sometimes be increased by bestowing special powers or additional resources to small numbers of individuals.

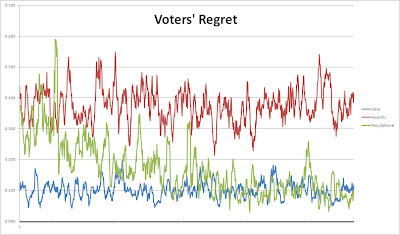

The question now becomes, can a reputational voting paradigm like the one I discussed in Building Ethos out of Logos actually result in a Pareto inequality and benefit the group as a whole by allowing the votes of those individuals with higher reputations to count more than others? To try to answer that question, I wrote a simple simulation. For the geeks out there, I'll describe the details of the simulation in a separate post. In general terms, it mimics the activities of five independent populations with 10,000 members in each. Props are proposed by randomly-chosen members and each member then votes on them based on its own internal preferences. A graphical summary of the results can be seen below. You might want to click on the graph to see the full-sized version.

The three plots display a measure of overall displeasure or regret after each of 1,000 props have been considered, voted upon, and either ratified or not. Regret is the inverse of social welfare, so lower regret numbers mean the system is doing a better job of identifying the population consensus. Under ideal conditions, when every voter is fully informed and there is 100% voter turnout, the result is the blue curve, which shows very low average regret. In other words, pure democracy works great when everyone participates and they have all the necessary information to accurately vote their individual preferences. Unfortunately, this is rarely the case for large populations.

The red curve shows what happens under more realistic circumstances, where only 40% of the population votes and only 25% of them are fully informed. Notice the overall regret numbers increase significantly, meaning more voters are more unhappy with the election results. The regret measurements include all voters, even those who didn't vote and those who didn't really understand what they voted for/against. As in real life, everyone has an opinion, even those who are too busy, too lazy, or too ignorant to express it by voting.

The green curve introduces reputational voting for the first time. We leave turnout percentage and informed percentage at 40% and 25% respectively, but each voter gets a boost in its reputation when it authors a prop that is eventually ratified by the population at large. Its rep is decreased when one of its props is rejected by the voters. Of course, each voter votes its current reputation, so voters who have more success historically in capturing the consensus of the whole group will eventually have higher reps and, therefore, disproportionately high voting power. As the green plot shows, this strategy starts off no better than the realistic scenario, but gradually gets better (lower regret numbers) until it has more or less completely compensated for the low turnout and poorly informed electorate. Thus, reputational voting does indeed implement a Pareto inequality by benefiting the population as a whole when additional resources (voting power) are granted to a small number of individuals.

There are other practical advantages of reputational versus representational (e.g. republics) systems that the simulation cannot show. Reputation is dynamic and continuously computed, which leads to a more robust system. Term limits are no longer necessary because reps increase and decrease over time based on recent history of constructive participation. Even when populations have shifting consensus opinions, which often happens, the reputation system is robust enough to shift with them. Also, reputation is computed as a side-effect of doing real work, proposing and voting on ideas, rather than as the side-show beauty contests representative elections often become. As I discussed in "Jane, You Ignorant Slut", it seems nobler to discuss ideas than people.

In order to bring democracy to the Internet, we will need to teach it to scale. As the above simulation shows, reputational voting is a straightforward mechanism that can help us do that.

No comments:

Post a Comment